I, on the other hand, stumble. Weak-kneed, I totter forward, still deluded that I chart my own course. I live a lie. I believe that I have matured, when I have only aged. I fancy that I have constructed my own history. It is all shit. The law is there. And in my last breath, like all lapsed believers, I will whimper and ask for forgiveness. I will die groveling, begging to be reinstated into the ranks I never truly left: the ranks of the law-abiding. Stupid me. I was a believer all along.

Goin’ Home, Goin’ Home, Mike Kelley, 1995

Mike Kelley’s stature as an internationally acclaimed American artist obscures his initial aspirations for a “planned failure”. When he set his ambitions on entering the art-world, Kelley claims that artists were vehemently despised, and so he was assured he’d become a bonified social drop-out. In this he failed miserably by pursuing and building on a career that made him an art-world luminary. However to the side of the institution he became are the remainders, a sprawling clusterfuck of activity – Kelley’s artwork.

The mythology of a resolved and glorified subjecthood was at core everything Kelley pushed his art towards unraveling. He found all social structures from built environments to one’s own identity, riddled with cracks, punctures, and fictions too obscene and pathetic to be ignored. It is in these fissures that Kelley resided, ultimately succeeding in kicking open a symbolic back door, inviting all manner of failures into the arena of his art-making. His art remains pungent, loaded with peripheral debris in both form and content. From the cryptic ‘Monkey Island’ series (1982-85) through to the pathological spectacle of ‘Day Is Done’ (2005-06), there remains no visible end to the abyssal complexity he let loose.

In Australia exposure to his work has been and continues to be scarce. His biography states he was in the Biennale of Sydney in 1984, two group shows at IMA, Brisbane in 2009 & 2011, followed with two tribute screenings of a video work at GoMA in early 2013. Apart from catching glimpses of his work in international art journals, it wasn’t until more seminal publications appeared in the mid to late 90s that Kelley’s work began to be more widely accessible. A common route of exposure occurred via the text ‘Return of the Real’ by art historian Hal Foster (1996), collaborative works featured in Paul McCarthy’s Phaidon publication (1996), and then Kelley’s own Phaidon publication (1999). With those listening to Sonic Youth, these loose threads reach back to their copy of ‘Dirty’ (1992) where Kelley’s stuffed animal photo portraits appear on the album’s packaging.

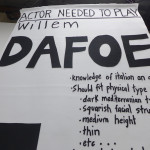

Despite this limited visibility Kelley’s art has had a profound influence across several generations of Australian artists. A Kitten Drowning in a Well bears witness to this fact. The tribute takes the form of a curated installation over both of 55’s gallery spaces, composed of new works by Carla Cescon, Ned Jaric, Ruth McConchie, Hany Armanious, Raquel Caballero, Matthew P. Hopkins, Ronnie Van Hout, Quinto Sesto, and Jesse Hogan.

In a third room adjacent to the galleries viewers will have the opportunity to see a selection of Kelley’s video works, most being debut features in Australia. The following will be screened throughout the duration of the exhibition:

– The Banana Man (1983)

– Blind Country – with Ericka Beckman (1989)

– Heidi (1992) – with Paul McCarthy

– Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstruction #1(Domestic Scene) (2000)

– Day Is Done (2005-06)

Exhibition by Iakovos Amperidis

A Kitten Drowning in a Well – Tribute Exhibition to Mike Kelley (1954-2012)

featuring – Carla Cescon / Ned Jaric / Ruth McConchie / Hany Armanious / Jesse Hogan / Raquel Caballero / Matthew P. Hopkins / Ronnie Van Hout / Quinto Sesto / Mike Kelley

21/11 – 14/12/14

Many thanks to the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts, and Electronic Arts Intermix for their generous support.