- Jelena Telecki

- Ecce Homo Homo

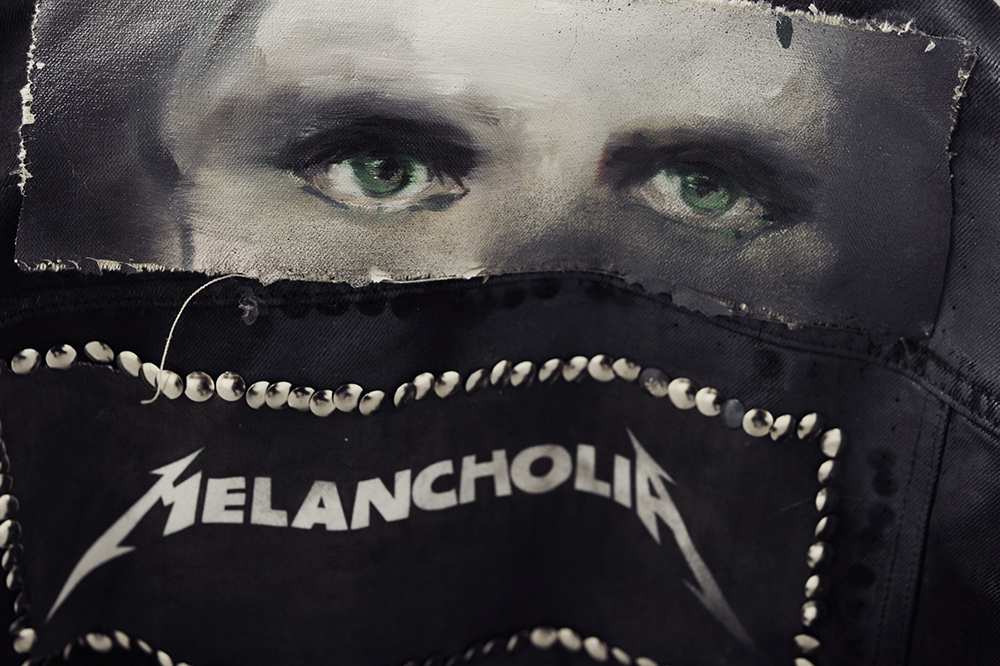

- Bubble Diagrams

- Love is Gold

- Piles

- I Starseed di Pasolini

- Big Cheese

- Opening Night (painter, sitter, muse)

- Constipation

- State Art

- Finally Lost

- Roland's Mother

- About

video- text

- page under construction / come back soon

contact Jelena Telecki: teleck@bigpond.com

ECCE HOMO HOMO

Jelena Telecki

27/10-19/11/2017

Bubble diagram, 2017

Various materials, various dimensions

Installation view: Artspace Ideas Platform

Photo credit: Zan Wimberley

Bubble diagram, 2017

Various materials, various dimensions

Installation view: Artspace Ideas Platform

Photo credit: Zan Wimberley

Ride, 2016

Oil on linen, 35 x 45 cm

Installation view: Artspace Ideas Platform

Photo credit: Zan Wimberley

Big Cheese!

Curated by Alex Gawronski and Justene Williams: Contemporary Art Tasmania, Hobart.

Artists: Stephen Birch, Alex Gawronski, Sean Kerr, Petra Maitz, Daniel Mckewen, Jelena Telecki, Justene Williams.

Constipation

Exhibited in “Casual Conversation, Verging on Harassment “, Minerva, Sydney, 2015

Artists: Anthea Behm, Guy Benfield, Ricarda Bigolin & James Deutsher,

Matthys Gerber, Hamishi Farah, Tim Johnson, Mary MacDougall, John Mawurndjul, Dave Pwerle Ross, John Spiteri, Jelena Telecki, Marian Tubbs

State Art

Installation view: NEW14, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne

Photo credit: Andrew Curtis

Works commissioned by Australian Centre for Contemporary Art

Leader, 2013

Oil on canvas, 45 x 55 cm

Photo credit: Lauren Eve

Work commissioned by Australian Centre for Contemporary Art

Collision 1, 2013

Oil on linen, 120 x 140 cm

Photo credit: Lauren Eve

Work commissioned by Australian Centre for Contemporary Art

Sailor, 2013

Oil on linen, 110 x 120 cm

Photo credit: Lauren Eve

Work commissioned by Australian Centre for Contemporary Art

Saturn, 2013

Oil on canvas, 50 x 65 cm

Photo credit: Lauren Eve

Work commissioned by Australian Centre for Contemporary Art

State Art (for NEW14, curated by Kyla McFarlane)

Artists: Charles Dennington, Andrew Hazewinkel, Taree Mackenzie, Daniel McKewen, Kenny Pittock, Danae Valenza, Jelena Telecki

Finally Lost (Various works, made in the period between 2010 and 2014)

Art is frequently understood foremost as a means of communication. Art makes the world clearer. From this perspective art is an inherently idealistic undertaking. As an idealist pursuit though, art inevitably leaves out much less palatable realities. Such art ignores too the intertwined ambiguities of lived experience and history, including the messy histories of art. Luckily other visions of art are vitally adept at approaching the disturbing, fleeting, uncanny and absurd. This is especially beneficial in an era like ours everywhere oppressed by functionalist demands for quantifiable ‘outcomes’ and uniformly positive results. Jelena Telecki’s art embraces many of those things that the supposedly rationally functionalist world ignores. Her work bears traces of history’s traumas and absurdities. It hints at art’s absurdity amidst historical trauma and the existential struggle of the individual to make sense out a world often promising nothing but a lack of guarantees. Art of this kind is an anathema and challenge to those who wish only to see shiny things, or who seek in art assurances of their control over life, the past and future. For Telecki, the artist and artwork are ultimately things among myriad things. The artist is thing-like in their refusal to state categorically ‘who they are’ avoiding the temptation to simply reveal biographical information in an age of constant social-media ‘revelations’. Art is a thing also, material, but not merely a commodity: art is a thing that symbolically substitutes the human, including the author. The Thing, like its b-grade horror film namesake, stands for every-thing positivism cannot account for. Even psychoanalysis, as a rationalising discourse, could never go the whole way to ‘cure’ or even adequately explain, humankind’s less-rational, less wholesome inclinations. What could be more valuable today then than an art that faces the absurdities of past and present and places some-thing in their way as a vital insight into our current less than clear situation?

Jelena Telecki’s works frequently allude in elliptical ways, to concrete historical and personal circumstances. In fact, these two dimensions, history and personal experience, are rarely separated: the historical cannot but impact forcefully on the personal. History however as it is normatively understood as objective fact, can never fully account for subjective experience. While history may seem to fulfil some sort of causal logic even at its most apparently senseless, the same cannot so easily be said of personal experience. Telecki left Yugolslavia during the 1991-2001 wars. Yet the artist never describes her experiences of these events outright. Nor does she attempt to journalistically explain them. In her work, traces of historical trauma assume an interior dimension that is sensed as part of a phantasmatic excess, an unreal Real stalking daily life like a dream or nightmare. Art as the language of the irrational and excess is purveyed against a dominant image of art as superior logic and clarity. Art speaks of those things that remain forever on the tip of one’s tongue like episodes in dreams when it becomes impossible to speak clearly - the words simply do not come. Even in a series of paintings like State Art (2014) where the presence of history is glimpsed via references to actual historical figures like communist Yugoslavia’s founding leader Josip Brod Tito, these images exist in relation to puzzling others that undermine any attempt to read an ultimate meaning to the narrative suggested. On the contrary, history has no answers and we rarely truly learn from historical example. In Telecki’s painting, Tito’s profile is partially occluded with green and yellow spots. These function as a deliberate visual annoyance, something that no matter how hard we try, we cannot simply explain away or eliminate. Are these spots holes or an uncanny superimposition of an alien planetary system? Do they indicate disease or is the image a kind of painted double-exposure that forces the historically incompatible worlds of figuration and abstraction together? They occlude in any case, a direct view of the subject, the Great Leader, whose face is already turned away from us. This recognisable face looks toward the future but speaks of the past. The temporal registers of past and future remain suspended in perpetual tension. In another large painting from the same series ‘J.P.P.’, a figure in full dress uniform reaches down toward what appears a gigantic pile of excrement. His face too is turned down and away, his identity mysteriously hinted at only by the initials of the work’s title: public composure is based on shit. The image we wish to portray publically defers secretly to those aspects of ourselves we cannot show, or cannot fully admit, or don’t even really know. Historical rationales of war, of occupation and exploitation, aim only to furtively prove that this is not the case and that leaders are always in control and always have our best interests at heart. In dreams on the other hand, we occasionally glimpse what cannot be said awake. In Telecki’s painting lurks something akin to Baudrillard’s notion of the ob-scene where the representational distance we are accustomed to via an image’s mediation, appears suddenly naked in all its obviousness. It turns out the emperor really has no clothes and the solid ground on which he stands is in fact, a pile of shit.

Telecki’s work also confronts art’s histories. She considers in particular the history of realist figurative painting. In her paintings, hints of the Old Masters are often discernible; a trace of Rembrandt here, a glimpse of Van Dyck (one of the artist’s professed favourites), there. These are no mere quotations however, nor are they straightforward homages. In fact, these ‘old world’ references appear in Telecki’s practice as if newly exposed to an entirely foreign world. At some point though this painted world must have begun to seem restrictive and the figures depicted, usually preoccupied by enigmatically ‘pointless’ actions, broke through the picture-plane. Three dimensional figures suddenly found themselves in direct confrontation with their painted counterparts. By no means a simple affair of exhibiting figurative sculptures alongside painted equivalents, Telecki’s figures seem instead as though dominated by the very conditions of their representation. In the exhibition Opening Night (painter, sitter, muse’ (2016) for example, a figure hooded in a sheet, stands alone stranded in a pair of lowly tracksuit pants into one of whose pockets a paltry $5.00 note has been stuffed. The figure balances a blank painting on its head while irreverently offering the audience a white-gloved ‘finger’. The empty painting is comparable to the unseen, unknown face we can only imagine beneath its sheet. The blank painting represents both content and nothingness; an object of potentiality and a pure painting/thing. The hooded (blinded) figure is similarly an empty cipher, essentially an ‘anybody’ or ‘nobody’, or perhaps more pointedly in this instance, a ‘some-thing’ or ‘any-thing’.

Here, this ghostly, veiled yet distinctly urban, figure faces paintings of idealised male nudes. Rather than veiled, these nudes are alternatively headless. The deliberately slack, amorphous smudge of brown paint that surmounts the neck of one in place of a head deliberately suggests the artist had simply given up, completely indifferent to the model’s identity. This gesture could be additionally read as a mordantly humorous retort to decades of images of headless female nudes in the canon of Western painting. More broadly, the scenario played out in this instance is one in which Telecki, as author, seems to watch sardonically over the situation she has created. It were as if the paintings, come to life, had landed in a situation whereby their newly embodied selves were endlessly trapped in attempting to figure out where they’d come from and why they were there. Meanwhile, the absented real artist looks on from the wings in wry amusement. In Love is Gold (2016) a figure kneels, ass up, its head stuffed invisibly into the seat of an armchair, a gesture symbolically reminiscent of the ostrich burying its head in the sand. Indeed, headlessness and facelessness are recurrent motifs in Telecki’s work. Either the head is covered, or wiped out, or buried, as it is here. Without a face or head, figures become things. They are things with recogniseable characteristics - clothing, posture, attitudes - but seem unidentifiable and lost.

Of course there is humour as well in Telecki’s artificial scenarios. It is a blackly absurdist humour of Beckettian, Kafkaesque or Gogolian dimensions. In Opening Night once more, a finely rendered image of a male nude stands poised over a pile of unfinished paintings. These have seemingly been discarded atop a pile of general rubbish; leaking paint tins, mattress stuffing, wood chips. The pallid though regal visage of a goateed nobleman from a bygone era peers from this ignominious heap, unceremoniously tossed aside to rot. In Love is Gold, a figure in a brown tracksuit jacket peels apart a painting which apparently depicts the erotic parable of Leda and the Swan, a classical subject beloved of art history. Here the dummy treats the painting literally like a window to the world. He gestures to circumvent the logic of representation by physically attempting to penetrate to what lies behind it. The exhibition Bubble Diagrams (2017) continues this thread and reads almost like Pygmalion in reverse. Instead of transforming eroticised representation into living flesh, the sculptural subject in question writhes on the gallery floor grasping a figurative canvas to it as though in masturbatory ecstasy. The canvas doubles as a shroud, again covering the lying figure’s face (if it indeed has one). Rising above the grappling mannequin is an attenuated painting of a fully shrouded figure in white. The reduced silhouette of this ghostly apparition looms above the abandoned figure below, forever unknowable, unreachable like a barely glimpsed memory. The central focus of this exhibition though is another mannequin standing atop a wooden crate. The crate hints at an imminent speech, an impending monologue perhaps denouncing the actions of the figure sprawled compromisingly on the ground. Such a speech will never occur however as the standing figure’s upper body, including its head, is encased in thick foam bound tight with packaging tape. Of course, this figure could never talk anyway as it a mere thing. Its packaged quality speaks to this fact. Such packaging references as well the thingness-of-art. Art, in its most acute manifestations, has always attempted to elude its reduction to mere objectification. Telecki’s practice continually grapples with this paradox, of an art that wants to be more than art, an art that aims to be affective beyond aesthetic considerations targeting the lazy delectation of commodity hounds.

The complexity of Telecki’s work lies in its deliberate and considered obliqueness, the power of its jarring juxtapositions and its dedication to unearthing the earthy, the palpably abject and seemingly senseless. Every positivist, every un self-reflexive do-gooder, finds it difficult to apprehend the underlying precarity of existence. For them, such a realisation is just a ‘negative’ obstacle to ‘success’, as far as success is perceived in the most predicable light of wholly external gratification. What is for sure is that ours are uncertain times. The inklings of future global catastrophes suggest themselves today in a variety of ways, political, social and ecological. Meanwhile, the persistent, inescapable fetish for the myth of economic rationalism – one (faceless) god to rule them all - continues to reap far-reaching irrationalist consequences on innumerable lives. Not least of these are the lives of artists whose ‘products’ continue despite everything, to be ambiguous by definition. Rather than shoring herself up in the safety of the clean and easily comprehensible, Telecki rethinks the art-thing. From a psychoanalytical perspective the Thing is dead and alive; it is always monstrous, indigestible, compelling as well as repellent. Facing the facelessness of the thing that stalks individual and collective psyches, Telecki’s art revels in its challenge to those who would believe the art question already answered.

Alex Gawronski Oct 2017

'NEW14' at Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), March 15 - 18 May 2014